This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

Over the past decade, Kenya has been a global beacon, celebrated for achieving near-universal access to life-saving HIV treatment. Today, a sudden stop-work order from a major donor has exposed a fragile reality, leaving over a million people, from seasoned peer educators to vulnerable children, asking one terrifying question: are we disposable?

The first sign of the panic wasn’t an official government memo or a public health announcement. It was a crude, terrifying graphic on prime time television newscast:

For Verah Awuor, a 25-year-old single mother and peer educator living with HIV, the sight felt like a death sentence directed squarely at her. Verah had contracted the virus as a teenager, but through years of counselling and consistent Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), she suppressed her viral load, even gave birth to a healthy, HIV-negative daughter. She was a walking, smiling testament to what Kenya’s HIV care, offered through the public health system, could achieve.

But success, it turned out, was built on a foundation of foreign aid.

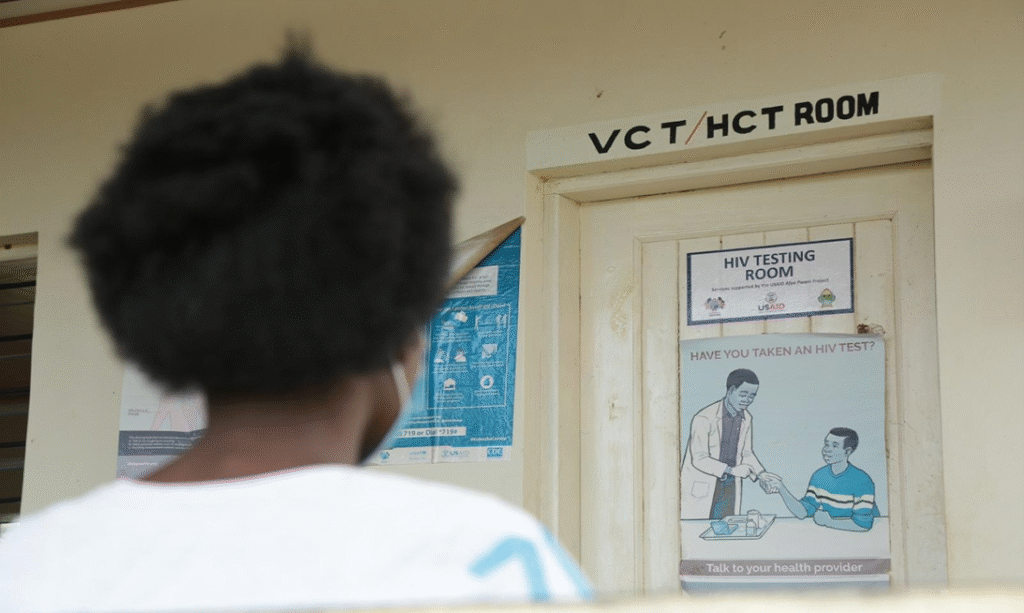

When US President Donald Trump issued an executive order on 20th January 2025, calling for a 90-day pause and review of all foreign aid, what followed was a US Agency for International Development (USAID) stop-work-order. This sent a predictable shockwave through the healthcare system. At the county hospital in Dandora, where Verah volunteers as a peer educator, panicked patients rushed to the comprehensive care clinic in numbers, demanding enough ARVs to last a year. Verah and her fellow volunteers had to lock themselves in rooms, acting absent, as they could only offer short-term supplies.

“Patients would come and demand for medicine. They would be like ‘give me medicine, I have seen the news,’” Verah recounts. The scarcity was immediate and profound. Patients who once received a six-month supply of life-saving medicine saw their allocation cut to one or two months, just so the clinics could ration the limited stock, over the period of uncertainty. For those on complex second-line ARVs, the situation was dire: stock-outs forced some of them back to first-line drugs, a situation with potentially fatal consequences.

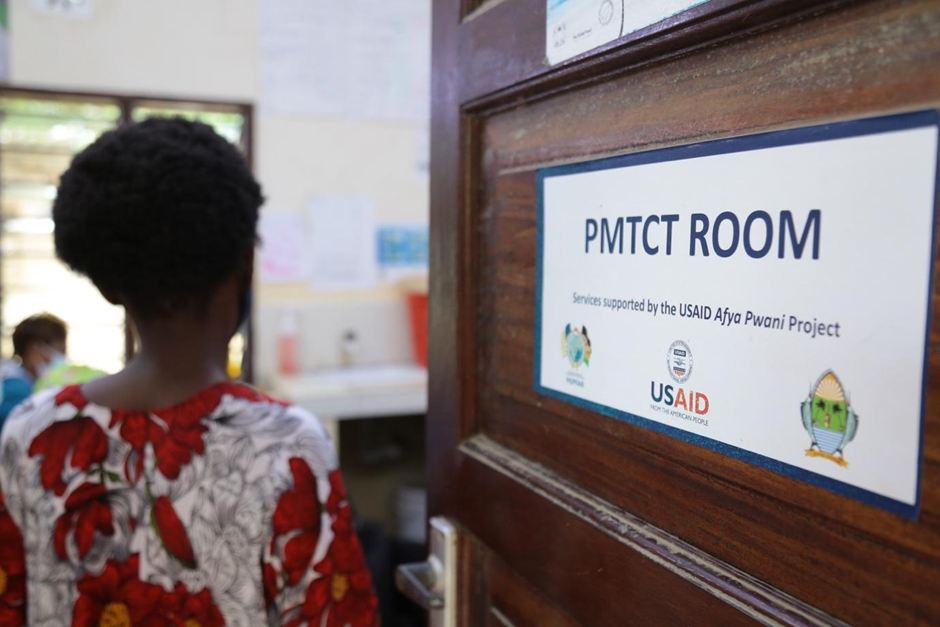

Even prophylaxis for infants born to HIV positive mothers, ran out. “A mother would come to the facility and ask, “should I stop breastfeeding my child?” There was that tension and you realise the child is just like 2 months old,” Verah recalls, the memory of that fear still raw.

A false victory

The crisis was not a failure of treatment, but a failure of foresight. According to the, Kenya has nearly achieved the global 95-95-95 targets set by UNAIDS (95% of all people living with HIV to know their status, 95% of those diagnosed to receive sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 95% of those on ART to have viral suppression). The country has an estimated 1,378,457 people living with HIV. Importantly, 97 per cent of those people are on Antiretroviral Therapy, and 94 per cent of those on treatment have achieved viral suppression. This phenomenal success, a viral suppression rate higher than many developed nations, is the “victory” now hanging in the balance.

The Report itself, however, highlights the underlying fragility. While celebrating a decade of progress, it acknowledges that AIDS-related deaths and new HIV infections remain unacceptably high. Further, it documents a severe, yet unaddressed, structural threat: Overseas Development Assistance for HIV, while providing 80% of the HIV-care commodities in Kenya, has declined by more than 50 per cent over the last five years.

This decline in international aid “has not been matched with an increase in government funding to bridge the widening financial gap” the report notes. This is the core tension: a medically successful program that is financially bankrupt, the result of years of political procrastination and a reliance on foreign benevolence.

Foot-soldiers Championing Successful HIV Care

Behind Kenya’s HIV care is a mighty army made of ordinary people. Men, women and young people living positively with the virus. Having attained viral suppression, they volunteer within their communities as educators and counsellors, to help others adhere to treatment. They’re the backbone to the entire system.

65-year-old Joseph Sadiki of Mafumbini village in Mnarani, Kilifi County, has been taking his ARVs for 21 years. His determination embodies the country’s long fight against stigma, a battle that claimed people close to him, when the disease was still a shadow, shrouded in shame and silence. Today, Sadiki is not just surviving; he is raising five children, all born HIV-free.

Sadiki who earns his livelihood working as a wood sculptor also volunteers as a community health champion at the Kilifi Referral Hospital, serving over 40 adults and 60 children living with HIV in Mnarani area. He fears the pauses and cuts on USAID funding could erode the gains made in the fight against HIV. “Many key programs in the community that were being supported by USAID are already closing doors. This is worrying because we could soon start seeing a sharp spike of new HIV infections, especially among young people”, he stated.

Verah, too, is a product of this system. These peer educators are the foot soldiers who link patients to care, maintain adherence, and conquer the stigma that still drives some patients to travel longer distances to seek care discreetly, rather than utilizing local facilities.

The World AIDS Day Report itself highlights this community-led model, noting that the success achieved is primarily attributed to “partnership models that brings communities at the centre”. Their tireless advocacy and efforts to counter HIV-related stigma were essential to the milestones achieved. Now, these very individuals, whose commitment made the 97% treatment coverage possible, are the first casualties of the manufactured crisis. With their interventions fully supported by USAID; from training to transportation, they may not continue beyond the funding withdrawal.

A Triple Threat

The cutbacks affect much more than just the supply of pills. They dismantle the ecosystem of care built around the patient. For Verah, the crisis meant the abrupt halt of specialized services like cervical cancer screening, a critical preventive measure for women living with HIV. For thousands of children, it was the collapse of the Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) support programmes, leading to spikes in high viral loads as their support networks vanished.

The loss of these integrated services is devastating, particularly for the youth. The 2024 Progress Report is explicit: 57 per cent of all new HIV infections in Kenya are domiciled among adolescents and young people aged 15-34 years. Young women (15-24 years) account for a disproportionate 31 per cent of new adult cases.

Furthermore, the same age group faces the triple threat: a devastating convergence of new HIV infections, unintended pregnancies, and instances of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The report notes that over 20,000 cases of SGBV among adolescents (10-17) were reported in 2023. By cutting comprehensive care, the financial crisis directly sabotages Kenya’s fight against this multi-layered threat, pushing a vulnerable generation back toward the shadow of the epidemic.

The fundamental issue is simple arithmetic: The Kenyan government still relies on overseas aid to finance the vast majority of its HIV program. The Progress Report confirms that while the country has seen accelerated efforts, it has simultaneously experienced a widening resource gap.

The Integration Mess

In response to donor pressure to achieve self-reliance, the government is accelerating a plan to integrate specialized HIV services into the general healthcare system. On the surface, this sounds like a mature public health strategy. In reality, experts fear it is a recipe for disaster. The integration plan carries the harsh mathematics of personnel cuts. Over 41,000 healthcare workers, including specialized HIV nurses, counsellors, and peer educators, who were previously paid through donor grants now face unemployment. If these workers are let go, the intellectual and social capital built over decades will vanish overnight. The system will lose the expertise required to manage complex second-line treatments, prevent mother-to-child transmission, and, most importantly, provide the high-touch community support that has kept the viral suppression rate at 94 per cent.

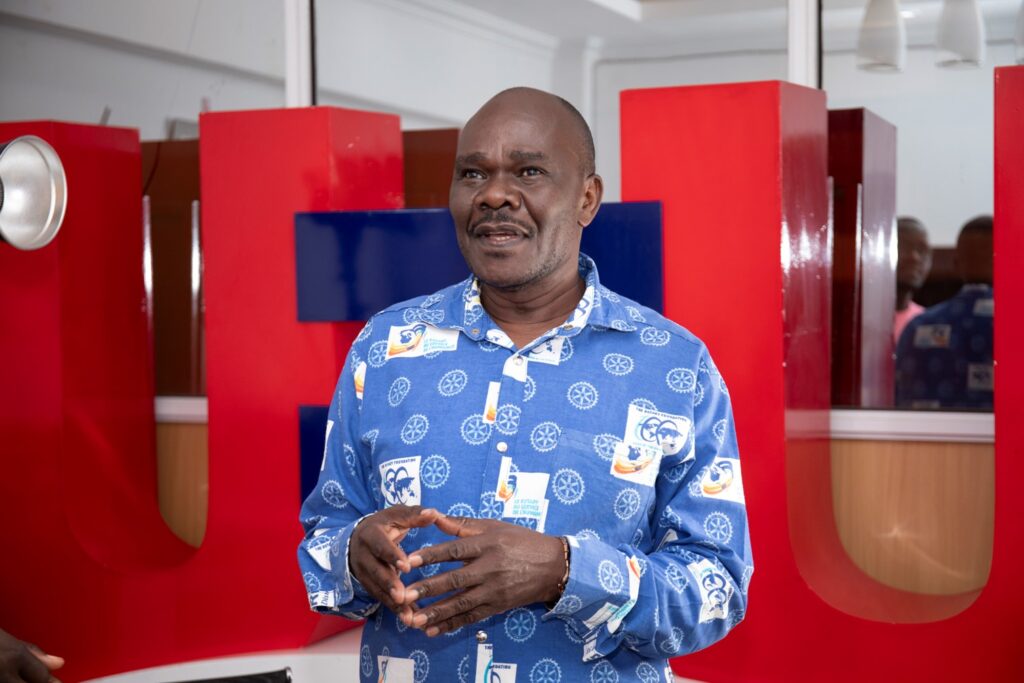

Nelson Otuoma, CEO of the National Empowerment Network of People Living with HIV in Kenya (NEPHAK), warns that what is unfolding is not just a funding gap, but a governance failure. “For twenty years, the government relied on donors to fund nearly everything, from drugs to data systems. When those donors pull back, the whole house shakes,” he says. “This is not a surprise. The signals were there for years, but we failed to prepare.” In addition, an already understaffed health system will struggle even more with integration of a service demanding patience and comprehensive support.

Maria Mulwa, Kilifi County’s HIV Services Coordinator, acknowledges the concern but insists integration is the only viable path. “We cannot afford to run parallel systems forever,” she says. “We are epidemic, the current situation feels like a betrayal.

Sadiki, the man who has spent 21 years on ARVs, directs his plea not to his government, but to the American authorities he sees as holding the ultimate power. “My life depends on the ARV drugs,” he said, fighting back tears. “Cutting off support for these services is like a death sentence to me and millions others. I have five children… if I die, how will their life be? I beseech you, think about us in your decisions”.

Verah, meanwhile, refuses to lament. She has joined a group of ten young mothers to sensitize her community on how to cope, using social media to maintain the continuity of care where the official system may fail.

For the over one million Kenyans living with HIV, the shelf-life of hope is measured not in years, but in the pills they can access, the clinics that remain open to them, and the political will to choose lives over ledgers. Kenya proved that the epidemic can be conquered with global partnership. The question now is whether the country, and the international community, will allow a hard-won victory to crumble through sheer neglect by design.